Quantitative Research Part II - Probability Distributions in Finance

Introduction to Quantitative Research in a Simplified Way

In this series, we will present Quantitative Research, a highly complex field where complex mathematical tools are used to deliver predictive value with regards to data (particularly, time series).

The aim of the series is to get you exposed to the key parts of quantitative research and its wide array of possibilities.

Probability Distributions in Finance

If descriptive statistics tell you what the data looks like, probability distributions tell you what you assume about reality.

Every quantitative model makes distributional assumptions. Most of them are wrong. Many of them are dangerous.

This article explains probability distributions from a market reality perspective, not an academic one. You will learn what distributions are used, why they are used, where they fail, and how to work with them responsibly in Python.

Why Distributions Matter More Than Models

A model is just a transformation of assumptions. If your assumed distribution is wrong:

Risk is mispriced

Tail events are ignored

Signals look better than they are

Capital is destroyed quietly

Before regression, ML, or optimization, you must answer:

What is the probabilistic structure of my data?

Random Variables in Finance

A random variable maps outcomes to numbers. In finance:

Returns are random variables

Drawdowns are random variables

Volatility is a random variable

Time between crashes is a random variable

Discrete vs Continuous

Discrete: trade counts, tick moves, number of limit hits

Continuous: returns, prices, log prices, spreads

Most financial modeling uses continuous random variables, even when reality is discrete. This approximation already introduces error.

The Normal Distribution

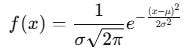

A random variable X is normally distributed if:

Defined entirely by:

Mean μ

Standard deviation σ

The Signal Beyond 🚀

From classic tools that have stood the test of time to fresh innovations like multi-market RSI heatmaps, COT reports, seasonality, and pairs trading recommendation system, the new report is designed to give you a sharper edge in navigating the markets.

Free trial available.

Why the Normal Distribution Fails

Empirical returns exhibit:

Fat tails

Skewness

Volatility clustering

Extreme events far beyond Gaussian probability

A 5-sigma event should happen once in millions of years. Markets produce them every decade.

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(42)

n_days = 1000 # length of time series

mu = 0.0004 # daily drift (~10% annualized)

sigma = 0.01 # daily volatility (~16% annualized)

returns = np.random.normal(loc=mu, scale=sigma, size=n_days)

from scipy.stats import norm

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

mu, sigma = np.mean(returns), np.std(returns)

x = np.linspace(returns.min(), returns.max(), 500)

plt.hist(returns, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.6)

plt.plot(x, norm.pdf(x, mu, sigma))

plt.title('Gaussian Fit vs Empirical Returns')

plt.show()If this fit looks acceptable to you, you are not looking at the tails.

Fat-Tailed Distributions

Markets are leptokurtic. Tail behavior matters more than center behavior.

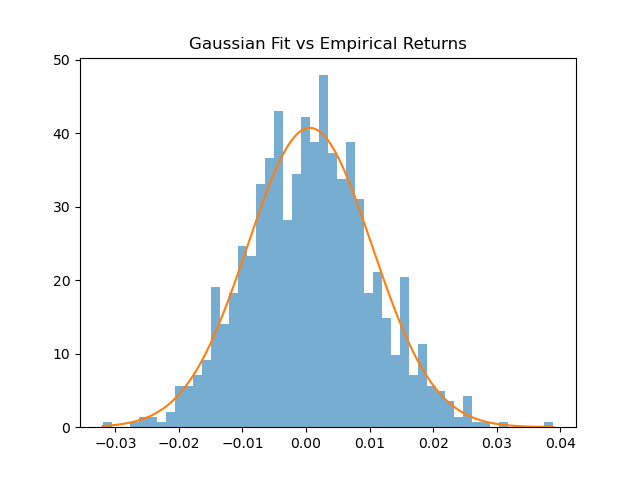

Student’s t Distribution

The Student’s t distribution is what you use when Gaussian assumptions break.

It looks like a normal distribution in the center and behaves very differently in the tails.

Where ν controls tail thickness.

Low ν → fat tails

High ν → Gaussian-like

from scipy.stats import t

df_hat, loc_hat, scale_hat = t.fit(returns)

plt.hist(returns, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.6)

plt.plot(x, t.pdf(x, df_hat, loc_hat, scale_hat))

plt.title(”Student-t Fit to Returns”)

plt.show()This already outperforms Gaussian assumptions in most markets.

Why t-Distributions Still Fall Short

Symmetric by default

Static tail thickness

No volatility clustering

No regime shifts

They are better. Not sufficient.

Skewed Distributions

Returns are rarely symmetric.

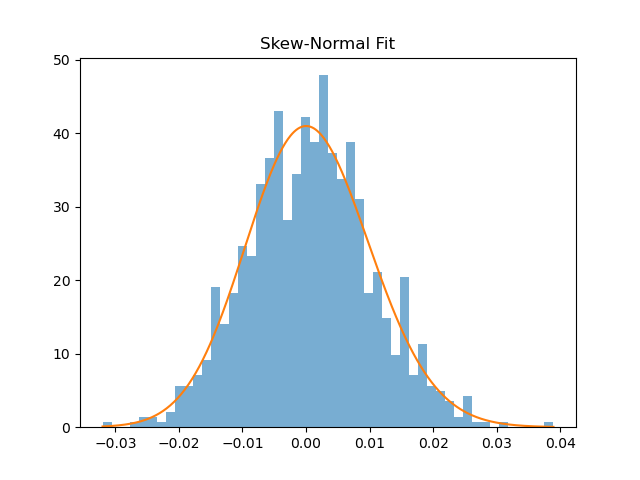

Skew-Normal Distribution

Adds a skewness parameter α. Useful for:

Option PnL

Carry trades

Trend-following returns

from scipy.stats import skewnorm

a, loc, scale = skewnorm.fit(returns)

plt.hist(returns, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.6)

plt.plot(x, skewnorm.pdf(x, a, loc, scale))

plt.title(”Skew-Normal Fit”)

plt.show()Still parametric. Still limited.

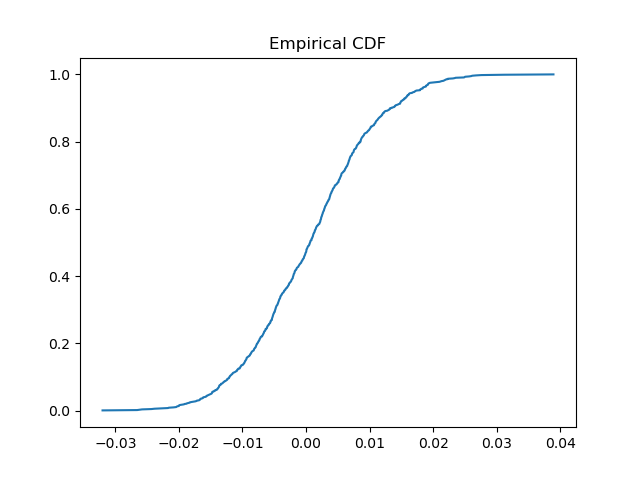

Empirical Distributions

The most honest distribution is the one you observe.

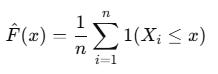

Empirical CDF

Empirical CDF (ECDF) is the data-driven version of a cumulative distribution function. No assumptions. No parametric model. Just the data.

sorted_r = np.sort(returns)

cdf = np.arange(1, len(sorted_r)+1) / len(sorted_r)

plt.plot(sorted_r, cdf)

plt.title(”Empirical CDF”)

plt.show()Empirical distributions are:

Noisy

Sample dependent

Honest about tails

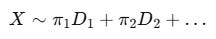

Mixture Distributions and Regimes

Markets are not one distribution. They are multiple distributions switching over time.

Regime Mixtures

Examples:

Calm regime

Volatile regime

Crisis regime

regime1 = np.random.normal(0, 0.005, 700)

regime2 = np.random.normal(0, 0.03, 300)

mixed_returns = np.concatenate([regime1, regime2])Single-distribution fitting hides this structure completely.

Conditional vs Unconditional Distributions

This distinction is critical.

Unconditional: full-sample distribution

Conditional: distribution given information

Examples:

Returns given high volatility

Returns given trend

Returns after drawdowns

Most alpha exists conditionally, not unconditionally.

Always ask: conditional on what?

Why Probability Assumptions Break Models

Let us be explicit.

Value-at-Risk fails due to tail assumptions

Sharpe ratios fail under skewness

Mean-variance optimization collapses under fat tails

Backtests lie when distributions shift

Distributional ignorance is the root cause.

Do you want to master Deep Learning techniques tailored for time series, trading, and market analysis🔥?

My book breaks it all down from basic machine learning to complex multi-period LSTM forecasting while going through concepts such as fractional differentiation and forecasting thresholds.

Get your copy here 📖!