Quantitative Research Part I - Introduction to Descriptive Statistics

Introduction to Quantitative Research in a Simplified Way

In this series, we will present Quantitative Research, a highly complex field where complex mathematical tools are used to deliver predictive value with regards to data (particularly, time series).

The aim of the series is to get you exposed to the key parts of quantitative research and its wide array of possibilities.

A Primer on Descriptive Statistics

Quantitative research does not start with machine learning, neural networks, or fancy predictive models. It starts with describing reality correctly.

Before you forecast, optimize, or trade anything, you must understand what the data is, how it behaves, and what it hides. Descriptive statistics are not a beginner topic. They are the foundation that silently determines whether every downstream model succeeds or fails.

Most failed quant models fail here, not later.

What Descriptive Statistics Actually Do

Descriptive statistics answer a simple but brutal question:

What is the data doing, without pretending it is smarter than it is?

They summarize, compress, and structure information without inference.

No prediction. No causality. No hypothesis testing.

In quant research, descriptive statistics serve four roles:

Data sanity checking

Regime identification

Feature understanding

Model failure diagnosis

If you skip them, you are blind.

Types of Data You Will Encounter

Before computing anything, you must know what kind of data you are handling.

Cross-Sectional Data

Multiple assets at a single point in time.

Examples:

Stock returns today

Volatility across assets

Factor exposures

Time Series Data

One variable observed through time.

Examples:

Price

Returns

Volume

Indicators

This is where most quant work lives.

Panel Data

Multiple assets observed through time.

Examples:

Equity universes

FX baskets

Macro datasets

Almost all institutional research uses panel data.

Measures of Central Tendency

Central tendency answers the question:

Where does the data live?

Arithmetic Mean | The most abused statistic in finance

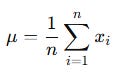

For a dataset x1, x2,..., xn:

The mean assumes:

Symmetry

No extreme outliers

Finite variance

Markets violate all three.

import numpy as np

mean = np.mean(returns)The mean of returns is often meaningless in fat-tailed distributions.

The Signal Beyond 🚀

From classic tools that have stood the test of time to fresh innovations like multi-market RSI heatmaps, COT reports, seasonality, and pairs trading recommendation system, the new report is designed to give you a sharper edge in navigating the markets.

Free trial available.

Median | The most underrated statistic

The median is the middle value after sorting. It’s important because it is

Robust to outliers

More stable across regimes

Better representative of typical behavior

median = np.median(returns)If mean and median diverge significantly, your distribution is skewed or polluted.

Mode | The most frequent value

Rarely useful for continuous financial data. Sometimes useful for discrete variables like trade sizes or tick data.

Measures of Dispersion

Central tendency without dispersion is useless. Dispersion answers:

How violent is the data?

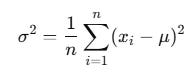

Variance

The mathematical representation of variance is as follows:

Variance penalizes large deviations heavily.

Python

variance = np.var(returns, ddof=1)Use ddof=1 for sample variance.

Standard Deviation | The square root of variance

This is what traders mistakenly call risk.

std = np.std(returns, ddof=1)Standard deviation assumes:

Normality

Linear risk

Symmetry

Markets do not care.

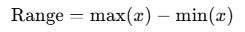

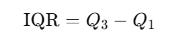

Range and Interquartile Range

The mathematical representation of the range is as follows:

Useless alone. Dominated by outliers. The interquartile range (IQR) is as follows:

q1 = np.percentile(returns, 25)

q3 = np.percentile(returns, 75)

iqr = q3 - q1IQR is your friend in noisy markets.

Shape of Distributions

This is where most quant intuition is born.

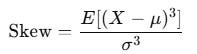

Skewness

Skewness measures asymmetry.

Positive skew: rare large gains

Negative skew: rare large losses

from scipy.stats import skew

sk = skew(returns)Most strategies die from negative skew, not low Sharpe.

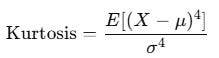

Kurtosis

Kurtosis measures tail heaviness.

Normal distribution has kurtosis of 3. Finance usually has excess kurtosis.

from scipy.stats import kurtosis

kt = kurtosis(returns, fisher=False)High kurtosis means tail risk is real, not theoretical.

Moments of a Distribution

Descriptive statistics are structured as moments:

First → Mean

Second → Variance

Third → Skewness

Fourth → Kurtosis

Most models implicitly assume only the first two matter. That assumption is usually wrong.

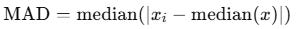

Robust Statistics

Markets are adversarial environments. Your statistics must survive abuse.

Trimmed Mean

Ignore extreme values.

from scipy.stats import trim_mean

trimmed = trim_mean(returns, 0.05)Median Absolute Deviation

The formula for this is as follows:

mad = np.median(np.abs(returns - np.median(returns)))MAD beats standard deviation during crises.

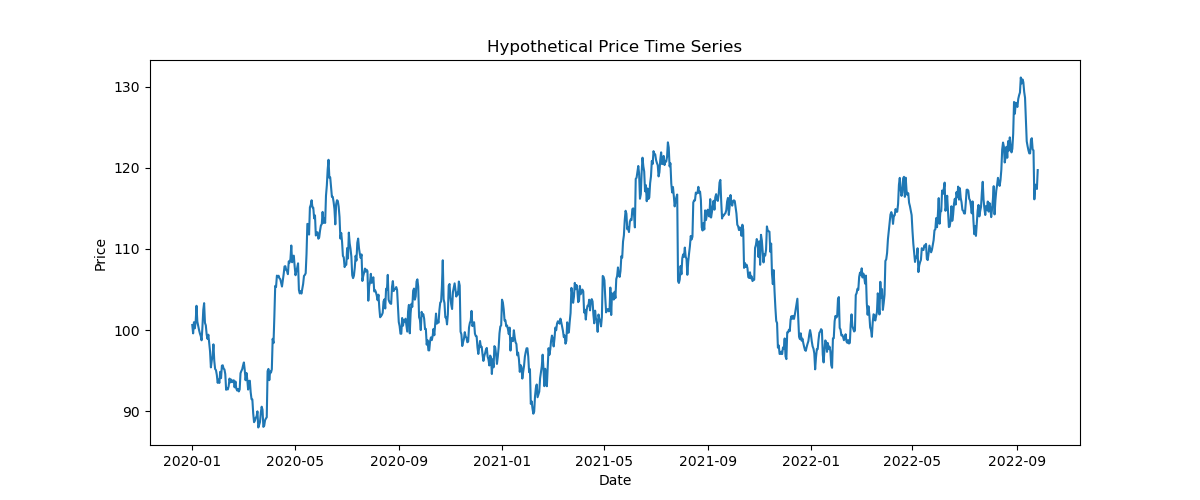

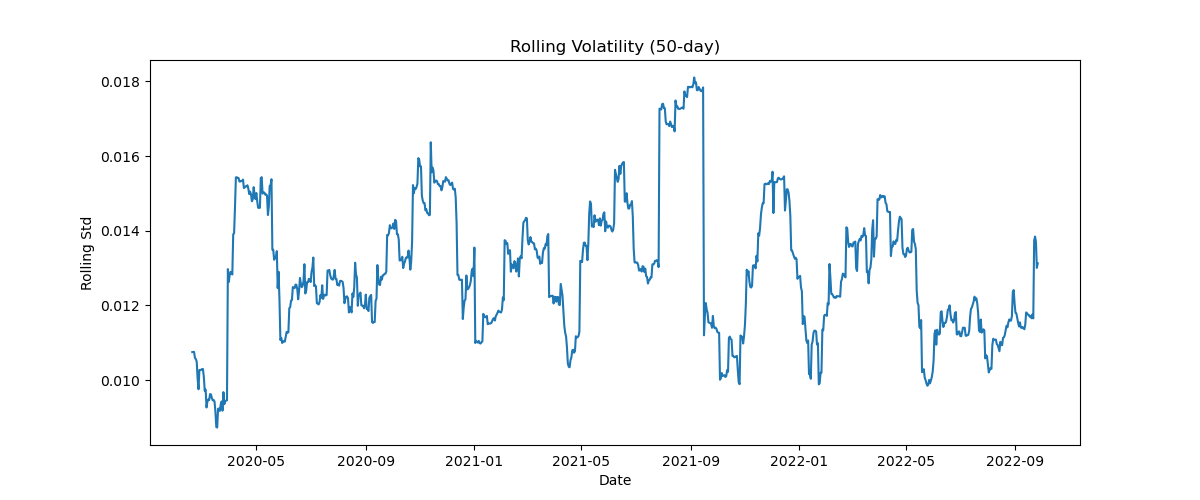

Rolling Descriptive Statistics

Static statistics lie in non-stationary markets. Rolling statistics reveal regime changes.

window = 50

rolling_mean = returns.rolling(window).mean()

rolling_std = returns.rolling(window).std()Let’s see all of this with an example:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import skew, kurtosis

np.random.seed(42)

n_obs = 1000

dates = pd.date_range(start=”2020-01-01”, periods=n_obs, freq=”D”)

# Simulate returns with fat tails (Student-t)

df_t = 4

returns = 0.0005 + 0.01 * np.random.standard_t(df=df_t, size=n_obs)

# Convert returns to price series

price = 100 * np.exp(np.cumsum(returns))

df = pd.DataFrame(

{

“price”: price,

“returns”: returns

},

index=dates

)

# Basic descriptive statistics

stats = {}

stats[”mean_return”] = df[”returns”].mean()

stats[”median_return”] = df[”returns”].median()

stats[”std_return”] = df[”returns”].std()

stats[”variance_return”] = df[”returns”].var()

stats[”min_return”] = df[”returns”].min()

stats[”max_return”] = df[”returns”].max()

stats[”skewness”] = skew(df[”returns”])

stats[”kurtosis”] = kurtosis(df[”returns”], fisher=False)

# Quantiles

stats[”q01”] = df[”returns”].quantile(0.01)

stats[”q05”] = df[”returns”].quantile(0.05)

stats[”q95”] = df[”returns”].quantile(0.95)

stats[”q99”] = df[”returns”].quantile(0.99)

# Robust statistics

median = df[”returns”].median()

mad = np.median(np.abs(df[”returns”] - median))

iqr = df[”returns”].quantile(0.75) - df[”returns”].quantile(0.25)

stats[”MAD”] = mad

stats[”IQR”] = iqr

# Rolling statistics (regime awareness)

window = 50

df[”rolling_mean”] = df[”returns”].rolling(window).mean()

df[”rolling_std”] = df[”returns”].rolling(window).std()

print(”\nDESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS (RETURNS)\n”)

for k, v in stats.items():

print(f”{k:20s}: {v: .6f}”)

# Visualization

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.plot(df.index, df[”price”])

plt.title(”Hypothetical Price Time Series”)

plt.xlabel(”Date”)

plt.ylabel(”Price”)

plt.show()

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.hist(df[”returns”], bins=50)

plt.title(”Return Distribution (Fat Tails)”)

plt.xlabel(”Returns”)

plt.ylabel(”Frequency”)

plt.show()

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.plot(df.index, df[”rolling_std”])

plt.title(”Rolling Volatility (50-day)”)

plt.xlabel(”Date”)

plt.ylabel(”Rolling Std”)

plt.show()mean_return : 0.000180

median_return : 0.000315

std_return : 0.013085

variance_return : 0.000171

min_return : -0.095929

max_return : 0.061775

skewness : -0.335217

kurtosis : 7.439154

q01 : -0.034367

q05 : -0.020559

q95 : 0.020284

q99 : 0.036200

MAD : 0.007211

IQR : 0.014354Do you want to master Deep Learning techniques tailored for time series, trading, and market analysis🔥?

My book breaks it all down from basic machine learning to complex multi-period LSTM forecasting while going through concepts such as fractional differentiation and forecasting thresholds.

Get your copy here 📖!